Laws of Motion - mobilisation techniques within Sports Massage and Sports Therapy

By Katie Campbell PGDip, BSc

As published in International Therapist Magazine

An introduction to Manual Therapy and Joint Mobilisations:

Manual therapy is another tool a therapist can use to manage pathology and dysfunction, techniques have been shown to decrease muscle tension, increase mobility around joints and reduce pain, it also works well in conjunction with other skills such as soft tissue therapy, muscle energy techniques, ultrasound and home stretches and exercises. In the following article the Maitland’s Concept will be discussed along with an example of how it can be used within a treatment using a holistic approach with a focus on clinical reasoning. In order to avoid confusion regarding the difference between different manual therapy techniques, it is important to clarify that high-velocity low-amplitude thrusts (HVLA), manipulations and adjustments can be defined by the ‘pop’ or ‘cracking’ noise which is thought to be the formation and collapse of gas, known as cavitation.

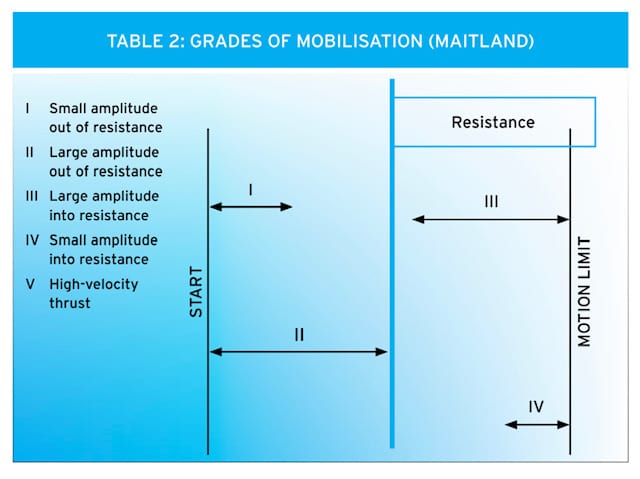

However, mobilisations do not involve a thrust and consequently don’t result in the classic ‘pop’ or ‘cracking’ sounds often associated with a chiropractor. The different grades of Maitland’s mobilisations work through I-IV, and accordingly the term grade V is commonly used for HVLA thrust by therapists. Within the category of mobilisations, physiological and accessory movements are discussed; Physiological movements are ways in which the client is able to move such as, flexion of the elbow and circumduction of the shoulder, whereas, accessory movements are movements in which the client is not able to move, such as a lateral glide of the humeral head or anteroposterior movement of a vertebrae.

‘If it’s important to the client, then it’s important’

-

The Maitland Concept includes assessment, examination and treatment of movement impairments by passive movement, this is not to say that this is the only way to treat musculoskeletal disorders, just one approach. This approach requires the therapist to remain open minded and have the capacity to empathise with the client, understanding what it is that the client is feeling and the impact that the disorder has on their lives. This could be pain during working hours whilst sat at a computer, or the inability to improve their swimming technique, as they are unable to get the appropriate range of rotation through their cervical spine.

The Examination:

When utilising mobilisations a through examination takes places, identifying if possible which movement reveals the disorder or to re-enact the exact movement which caused the injury. It is then possible to break the movement down and analyse the different components, thus making clinical sense of the joint movements and pain responses.

The therapist can consider the precise areas indicated on the client’s body, the depth at which the symptoms are experienced, along with other areas of pain and whether they overlap or are separate. Testing the joint and muscles allows the therapist to deduce how the symptoms change in response to movements or the different joint positions in other regions of the body.

If the clients pain is felt at the end of range (EOR) then consider when in that movement do the symptom first appear and does this vary with the continuation of the movement?

During the symptomatic range what manner do the symptoms behave and does muscle spasm?

Is there resistance and if so is there a relationship?

Other considerations during an examination with a client who feels pain during the whole range of the movement, are when in the movement does the pain increase and then if the limb is taken just past this point how is the intensity and referral of pain affected?

When watching the client perform these movements it is helpful to note whether it is a normal physiological movement using the range it has or is there stiffness apparent, potentially from a protective muscle spasm.

As mentioned previously the client is unable to perform accessory movements themselves so these are tested by the therapist using palpatory techniques, similar information is then gained.

Three main positions are used; the neutral/mid-range, a loose-packed position and the end of the available range. The neutral range is the mid way point such as flexion and extension, left and right rotation and distraction and compression. The loose packed position is where the client’s symptoms begin or begin to increase.

Palpation can identify soft tissue abnormalities along with symptomatic responses to the movement being performed, this information is deemed as important as the movement test themselves. The therapist can apply a logical analysis when both the physiological and accessory movements are performed together, the movement then can be used to differentiate between a group of movements.

An example might be when a client presents with pain during a supinated outstretch arm; it is possible to determine where and when the symptoms increase depending how the therapist pronates, supinates or distally and proximally whilst supporting the hand. When the pain increases during passive pronation 2o – 3o of the distal radio-ulnar joint, the pain is coming from structures within the wrist as the movement made by the therapist is increasing supination stress at the radio-carpal and mid-carpal joints.

However, if the source of pain is coming from the distal radio-ulnar joint then the pain would increase as the therapist applies supination at that joint. This logical ordered procedure can be used not only for other joints providing additional evidence leading to effective treatments but also during the subjective part of the examination.

Think about what the client is explaining and relate it to every day life, for example they might say “I feel pain in my low back”, the therapist might get a negative result when asking the client to bend forward and touch his toes, testing lumbar flexion and the same result when testing other structures around the pelvis. When relating this pain to everyday movements, such as pain when getting into the car, might highlight that cervical flexion could be the movement that triggers pain, therefore a slump test would be more appropriate in revealing the movement which re-enacts the symptoms.

Developing a Treatment Plan:

After a through examination a treatment plan can be developed, this might also include plans for subsequent treatments. If mobilisations are to be used it is vital that they are always performed pain free, therefore an assessment movement takes place before every set in order to determine at what point in the range the symptom is initiated, it is then that the grade of the movement can be determined. When performing Maitland’s mobilisations on a joint it is also helpful to document the number performed and the grade of each technique, that way analysis when discussing progression or regression with the client is clear.

As pictured below it can be seen that Grade I is a very small movement, taking the joint just out of resistance, for example abducting a client’s femur just 5o in a side lying position by holding above the knee, this oscillation is very small.

An example of a grade II mobilisation would be taking this same movement further but not as far that resistance is felt, this is a large oscillation as is grade III, but there will be some resistance felt.

And a grade IV oscillation remains within resistance and is small similar amplitude to that of grade I.

As noticed by the subtle differences between the grades it is imperative the therapist is engaged and uses their palpatory skills, allowing a precise technique which can be recorded and if appropriate reinitiated in future sessions.

Case study:

A 58-year-old male sought treatment presenting with pain referring around his left shoulder, and down his left arm to his fingers. His medical history includes C7 disc prolapse around 2 years previously and during this time he sought treatment from a physiotherapist, the symptoms decreased slightly but have continued to remain constant until recently when he noticed increased in severity and irritability. His occupation requires him to drive for up to 6 hours most days but is usually fit and well. Hobbies include cycling and walking, although at present he is unable to ride a bike as it incites symptoms.

A posture assessment concluded a forward head, this is not optimal and adds 10lbs of weight to the head per inch it sits away from it’s neutral position, hence increased strain throughout the supporting musculature, also increases compression through the cervicothoracic junction. A Dowager’s hump can be a result of this type of posture, which is the lump seen at the base of the neck and it thought to occur due to long periods spent driving or sitting at a desk with a head forward posture. The client described his symptoms as ‘tingling’ and ‘shooting’ which radiates down the back of his arm, numbness in his hand and around his thumb is noticed sporadically, however the pain around his shoulder was more of an ache under his shoulder blade mainly felt through the lateral aspect.

The therapist can deduce from the pattern of symptoms that the radial nerve is in some way compromised, testing the radial nerve was seen to increase symptoms dramatically and confirmed this. Flossing the nerve decreased symptoms by easing neural tension and reduce the hypersensitivity which can be the result of overused muscles thus increasing tone. Using the testing position the therapist ‘flossed’ the Radial nerve, this was implemented by flexing and then gradually increasing the extension of the wrist, keeping constant communication is essential as to not exceed the range where the client can tolerate the increased symptoms.

Restricted movement at end of range abduction-adduction of the humerus along with pain during cervical extension was noted. Along with nerve flossing the treatments utilised the use of soft tissue therapy through the hyper tonic muscle which included: The erector spinea group, supraspinatus, upper trapezius and scalene group and then over the deltoids, pectorals, and down triceps. This was performed in a side lying position due to the increase of pain when in prone.

Cephalad traction and longitudinals mobilisations were performed. These mobilisations were performed upwards the head, as opposed to the caudad which is a movement directed at the feet.

Traction is held for a short period of time, and when doing so, it is useful to encourage the client to breath, as commonly their breath is held which does not aid the parasympathetic nervous system.

All of the movements are required to be pain free and have been shown to improve function of the deep muscles within the neck. These techniques were used to increase space between the vertebrae, reducing tension as it gently ‘stretched’ the spinal column, the clients head was held securely at the base of the occiput, the mastoid processes can be used as to not ‘slide off’ the skull, the other hand supports under his chin, traction was held for 10 gentle breathes. Grade III longitudinal was deemed optimal after reassessment and used 3×20 times and this was repeated twice per treatment, grade IV became pain free during the course of treatments thus reducing the range of the oscillations which remained at the client’s end of range.

To enhance the treatment home exercises were given, these promoted a lengthened spine which encouraged movement at the occipitaloatlantal joint, along with improving the hip hinge pattern, restoring natural spine curvature which ideally results in pain free movement, specifically during commuting for work and cycling.

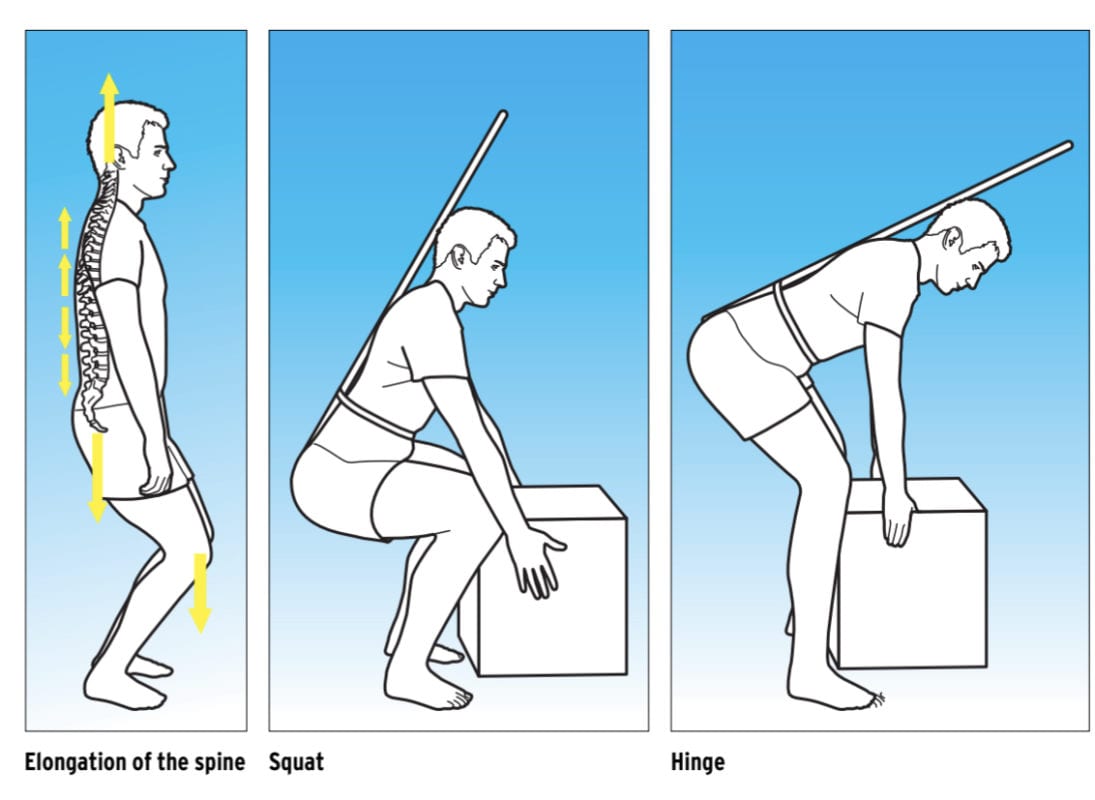

Using soft knees and a tucked under tailbone against the wall and then using the ‘red dot’ cue from the Alexander technique, a stretch down his back was felt, this he was asked to use 3-4 times a day and when possible to hold this position for 5-10 gentle breathes.

The Alexander technique describes the red dot to be above your head and around 3 foot in front of you, although it can not be seen as it is the crown of your head which is facing it. The client progressed to using a pole that rests on head and tail bone which keeps the previous position but also allows a hip hinge, this was practised standing about 30cm away from a wall and the bottom of the pole touches the wall if the movement is performed correctly, if the client is quadricep dominant than they try to squat which involves knee flexion, as identified in the picture below the hip hinge does not. At first the client was unable to lengthen his cervical enough to touch the back of his head to the wall or pole, gradually with manual therapy, adherence to home stretches and weekly treatments this is now possible and we hope soon he will be get back on his bike pain free.

By Katie Campbell BSc, PGDip

Katie is a graduate Sports Therapist and has worked within team based sport for many years since graduating from the University of Bath.

Katie runs her own clinic Enhanced Movement and teaches on several courses for Core Elements Training, which include the Manual Therapy and Joint Mobilisations CPD short course, along with Level 3 and Level 4 Sports Massage Therapy.

To find out more about our Manual Therapy and Joint Mobilisations CPD short course please visit: www.coreelements.uk.com/manual-therapy/