Dry Needling for Injury treatment and soft tissue disfunction

By Dawn Morse MSc

As published in International Therapist Magazine

An introduction to Dry Needling and use within injury treatment for soft tissue disfunction:

Both Western Medical Acupuncture and Dry Needling are commonly used as a clinical treatment modality for the use of a range of soft tissue injuries and conditions. Most people know what type of treatment acupuncture, be it traditional or medical, entails. However, many have not heard about Dry Needling as a treatment or are unsure about how Dry Needling differs from acupuncture.

Western medical acupuncture is a therapeutic modality involving the insertion of solid filiform needles. It is a modern adaptation of traditional acupuncture that is evidence based and widely researched. Western medical acupuncture is mainly practised by health care professionals and therapists, such as Chiropractors, Osteopaths, Physiotherapists, Sports Therapists and Sports Massage therapists as this modality is based around the treatment of pain, dysfunction, or injury. Although both Western medial acupuncture and traditional acupuncture are drawn from the principles of Eastern medicine and can successfully treat a range of conditions through needle insertion to key acupuncture points and through the stimulation of meridians. Training differs, however, as the traditional acupuncturists training is extensive and often involves training to diploma or degree standard with roots based on traditional practise, whereas western medical acupuncture is an extension of medical or injury-based training, and needle-based training is usually completed via a continuous professional development (CPD) course.

Dry Needling on the other hand is a modality that is also utilised by healthcare professionals and therapists to treat of musculoskeletal conditions, such as chronic pain, muscular tension, and dysfunction along with tendon injuries for example. In likeness with western medical acupuncture, training in Dry Needling is usually covered through the completion of CPD courses once qualified as a health care or therapy professional. Even though acupuncture and Dry Needling share a common tool, there are no historical ties with acupuncture.

Origins of Dry Needling:

Dry Needling is an invasive technique, that originates from medical research-based conclusions, with early work dating as far back as the early 1940’s.

Research by Doctors Janet Travell and David Simons in the early 1940’s sought to investigate the use of needle-based therapy on the treatment of muscular trigger points. Prior to the start of their research using needling techniques, it was known that trigger points could cause many symptoms and can be active or latent in the way that they present. For example, active trigger points can spontaneously trigger local or referred pain. They cause muscle weakness and restricted range of motion. Latent trigger points on the other hand do not cause pain unless they are stimulated, but they may alter muscle activation patterns and contribute to restricted range of motion.

Origns of Dry Needling and Research:

During research various substances including corticosteroids, analgesics and saline were injected using a wet needle into both active and latent trigger points.

Wider use of Dry Needling started after a study in 1979 by Doctor Karel Lewit, who concluded that it was the ‘needle’ that had a reducing effect on trigger point symptoms and not the injected substance. This led to a developmental change from ‘wet’ to ‘dry’ needling.

Numerous medical studies have supported the conclusions of Doctor Karel Lewit and found no difference between injections of different substances and Dry Needling in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain. In addition to this research has found Dry Needling to be most effective when a local twitch response is elicited. This response can often take the form of a wave flowing through the tissue, a jump or a pulsing action within the tissue. It’s theorised that this response leads to a rapid depolarization of the effected muscle fibers. After the muscle has finished twitching, the spontaneous electrical activity subsides, and the pain and dysfunction decrease dramatically.

Further research has identified that the positioning or twitch response technique, has been found to provides faster results in a clinical setting, especially in the treatment of chronic pain conditions, and it has led to decreases is muscular pain by 50% or more in one or two sessions, for the treatment of chronic lower back pain (Kauchman & Vulfsons, 2010).

Where trigger points are too sensitive to treat, distal needling can be utilised in these complex cases, as research has identified a significant decrease in pain immediately after needling, when needling distal to the actual site of the trigger point (Vulfsons, Ratmansky & Kalichman, 2012).

Although a wealth of research has sought to investigate the use of Dry Needling for the treatment of trigger point use, Dry Needling can be used in the treatment of many conditions such as those outlined below.

Benefits of dry Needling:

Reduction of acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain,

Reduce dysfunction and muscular tension,

Increase localised blood flow,

Increase range of motion,

Can be used to treat fascia, muscle tissue, tendon, and ligament injuries.

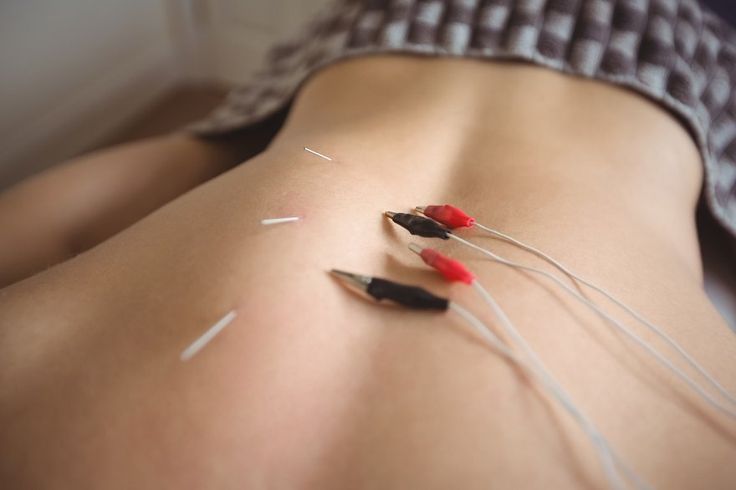

When used in conjunction with electrical stimulation Dry Needling

can also be used to treat:

Tendinopathies,

joint pathologies, such as arthritis and disc degeneration,

along with neuropathy,

post-operative pain and phantom limb pain.

Needle Use Within Treatment:

From the perspective of a therapist, Dry Needling can be used as part of a combination treatment, where massage, Dry Needling and wider modalities are used together to create a rounded programme. This is a great way to increase productivity within your clinical sessions and to maximise time if you have multiple areas to treat within the same session. This is also a useful way to reduce the amount of heavier pressure needed to treat more specific points.

For example, within a combination treatment for generalised back pain, after subjective and objective testing, treatment may start with manual massage techniques. After palpation and warming up the back with foundation massage, it may become apparent that the client has several active trigger points in the upper trapezius region. Rather than applying heavier pressure or the manual trigger point technique, Dry Needling can be used to reduce the muscle tension associated with these trigger points. In this instance, the medium covering these points would be removed and needles would be inserted.

Whilst the needles are inserted and reducing tension, massage could continue to wider areas of the body that do not interfere with activation of the needles, such as the gluteal or the hamstring region.

Dry cupping could also be used whilst the needles are placed in trigger points within the upper trapezius region. In this instance static vacuum cups could be used on wider areas of tension within the back region. Static cupping is preferable near the insertion of needles as movement is not used within this technique and therefore the needles will not be unnecessarily activated. Alternatively Hot Stones could be placed over wider areas of tension within the back, whilst the needles are inserted. Once the needles are removed, manual massage to the wider back area can recommence.

Dry Needling can also be used as a stand along treatment, where the therapist will collect subjective and objective data prior to treatment being applied with the use of needles only. In this model, the needling areas for injury should be considered along with the amount of time needed for treatment. Like that of manual massage or combination treatment, the treatment area should consist of the site of injury, areas above, below and on the opposite side of the injury should be treated where possible. Post treatment testing should also be used to assess effectiveness.

The use of needles within a treatment can result in a more relaxed atmosphere, as although this modality has a strong effect on the body, the client often finds the modality relaxing and less uncomfortable, when compared to the use deep tissue or sports massage application. In addition, the application of this modality is less taxing on the therapist.

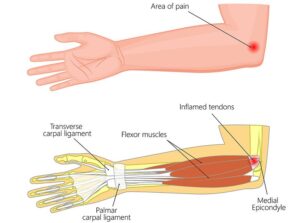

Example treatment: Medial Epicondylitis (Golfers Elbow)

Client presented with what appeared to be chronic medial epicondylitis. Subjective pain scale at the site of maximal tenderness was a 7 out of 10 (close to the site of the medial epicondyle of the humerus), and objective range of motion and muscle testing were consistent with the findings of medial epicondylitis.

Testing consisted of Active, Passive and Resisted flexion and extension at the elbow joint, along with wrist flexion, extension, ulnar and radial deviation.

To eliminate any secondary or contributing factors the shoulder range of motion testing was also completed.

Muscle testing involved looking for increased symptoms of pain and weakness in both the wrist flexor and extensor groups.

Typical symptoms of injury:

Pain and tenderness. Usually felt on the inner side of the elbow. Pain sometimes extends along the inner side of your forearm and typically increases such as receptive flexion and extension. Numbness or tingling sensations might radiate into one or more fingers.

The elbow joint may feel stiff and on testing there may be weakness in the hands and wrist.

Treatment:

As this injury was now three months old and had gradually been getting worse, treatment started with manual massage to the forearm region, to include massage to the wrist flexor and extensor groups, along with massage into the hand, and upper arm, to include the deltoid, triceps and biceps. Massage identified several areas of hypertonic (tight) areas along with several trigger point. As the forearm region was quite sensitive, Needles were the preferred use for helping to reduce the activation of the trigger points and muscle tension.

Needles were inserted primarily into active trigger points on the flexor carpi radialis and the pronator teres, along with wider areas within the flexor and extensor group. As the client had good muscle tone and was of overall good health, medium sized needles were used.

In addition, further points in the deltoids and triceps were treated with needle application.

The needles were left for a few minutes, before any activation occurred, as all needles were felt by the client on insertion. Whilst they were left, massage was applied to the non-injured side, as often tension is found in both arms. Whilst massage was continuing, on the non-injured arms, the needles on the injured side were activated every few minutes after feedback has been assessed. Activation methods included: flicking, turning and peppering techniques.

After the needles were removed, the area was re-assessed through palpation, and followed by connective tissue release, prior to finishing with further effleurage to the full arm.

Kinesiology Taping is a great way to finish this type of treatment, as it can help with continued pain relief and maximise circulation to the area. However as this was treatment one, this was postponed to treatment two, so that the effects of massage and needling could be assessed.

Post treatment testing identified a reduction in pain scale from 7 to 4 out of 10, and pain free range of motion at both the elbow and the wrist increased, which were all promising signs after just one treatment.

Home care activities:

Home care activites to help to maximise on the benefits of the treatment provided. This included the recommendation on contrast therapy through the application of hot and cold packs (2-minute swap between hot and then cold pack), twice a day for 10 – 20 minutes. Contrast therapy is useful as it can help with main management, increasing local circulation to the injury site, and reducing muscle tension through the blood shunting effect. Active rest from any aggravating factors was advised along with, wrist flexor and extensor stretches to be complete daily and held for about 15 seconds plus.

By Dawn Morse BSc, PGCE, MSc,

Dawn is a sports science and therapy lecturer and the director of Core Elements Training. Core Elements Training offers a range of accredited qualifications and short courses, including Level 3 & 4 Sports and Remedial massage therapy, Level 5 Diploma in Sports and Clinical Therapy and CPD short courses such as Dry Needling, Dry Cupping, Manual Therapy, Electrotherapy and Rehabilitation. To find out more about Core Elements accredited CPD short course in Dry Needling please visit the course page by Clicking Here.